I wasn’t expecting to be moved as equally by the simplest, purest expressions, as by wild innovation. Interest created by the decision to continue the curve on a muslin pattern, held the same weight as a big splash effect using magnets to pull metal powder in different directions. This was the mesmerizing tension of the Met’s Manus x Machina exhibit, exploring the continuum of hand vs. machine.

Representing the machine side, Dutch designer Iris van Herpen’s fantastical dreams spoke to the heart. There was nothing automated or distant about these masterpieces. Her genius shatters any notion that fashion doesn’t belong in a museum. In fact, going a step beyond sculpture, her creations rely on motion of the human form to come alive. One of her avant garde dresses could have risen out of the sea, looking like eroded limestone reefs with the silhouette of Penguin’s flipper. In the process, metal powder was combined with rubber and poured onto cotton fabric. The magnets are placed above and below it and pulled apart before it sets, creating peaks. Another more feminine Herpen dress is fabricated completely from 3D printing, and brings to mind the hand wrought glass of Dale Chihuly.

Fashion is just one of the artistic vehicles Hussein Chalayan uses to collaborate with science and design. Like a fairytale, his mechanical Kaikoku dress delights with birdies hugging the slope of a rigid gown. When deployed, they dart off the garment like single snowflakes being whipped around by the wind, only to open up and ascend like birds. Falling gently back to earth it’s like big feathers falling, but up close they resemble whirligigs with big crystal drops that flash in the sky.

The industrial, machine-made Colombe dress, by Issey Miyake, has elements of a white chocolate-ruffled wedding cake melting into what looks like molten rubber.

Miyake said, “One of my dreams was to see if we could make clothing without conventional tools, such as needles, threads and scissors. Here is the result: the fabric is woven monofilament; it is cut by heat and put together with snaps and leather straps. I named it Colombe after the dove, a symbol of peace.”

House of Dior’s Bar Suit Jacket from 1947, represents automation commanded by pure art form. Without shiny or textured distraction, it is the highest expression of talent to bring beauty out of the most pared down design. The artist has only the hand of line and proportion to make a statement.

Named Demi-Couture, by Martin Margiela in 1997, for taking a further step down to deconstructed, shabby couture. The machine-made is more reliant on details to bring life to the bare form. Here (mannequin far left) the worn hand of time adds a patina; stenciling and the hidden gleam of hook and eye bring a familiarity to which we’re drawn. 18 years later with John Galliano at the helm of Maison Margiela, he distresses, stains and adds black-lacquered toy cars to travel on this barren landscape.

In an extravagant profusion of buds, camellias and frothy feathers, one of the few completely handmade pieces in the Manus x Machina exhibit, was also among the most decadent. The House of Chanel Autumn/Winter 2005 showstopper is encrusted with 2,500 flowers, white ostrich feathers, and hidden, scattered sequins to catch glints of light. The wedding ensemble took 700 hours to make.

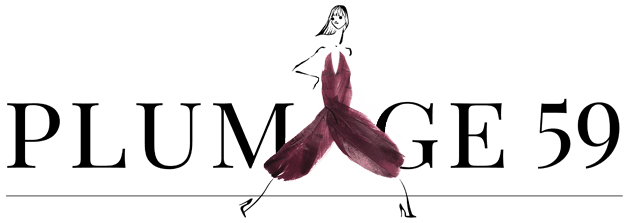

An early exemplar of the Met’s exhibit theme of hand and machine existing not in opposition, but on a continuum, was the Dior White Elephant dress from 1958. In Yves Saint Laurent’s first collection at the House of Dior, he called this glorious dress L’Elephant Blanc, in part to have a laugh at the expense. In an exquisite combination of design, construction and fairy hands, it is the dazzling sparkle of light from crystals, paillettes, sequins, and rhinestones that says it all.

The irony of a delicate material being machine-created, and an edgy result from hand-wrought technique is gorgeously represented in Valentino’s Spring/Summer 2016 piece. The column of lace supporting the evocation of a Roman gladiator war skirt confuses the eye just enough to focus, then move down in splendor.

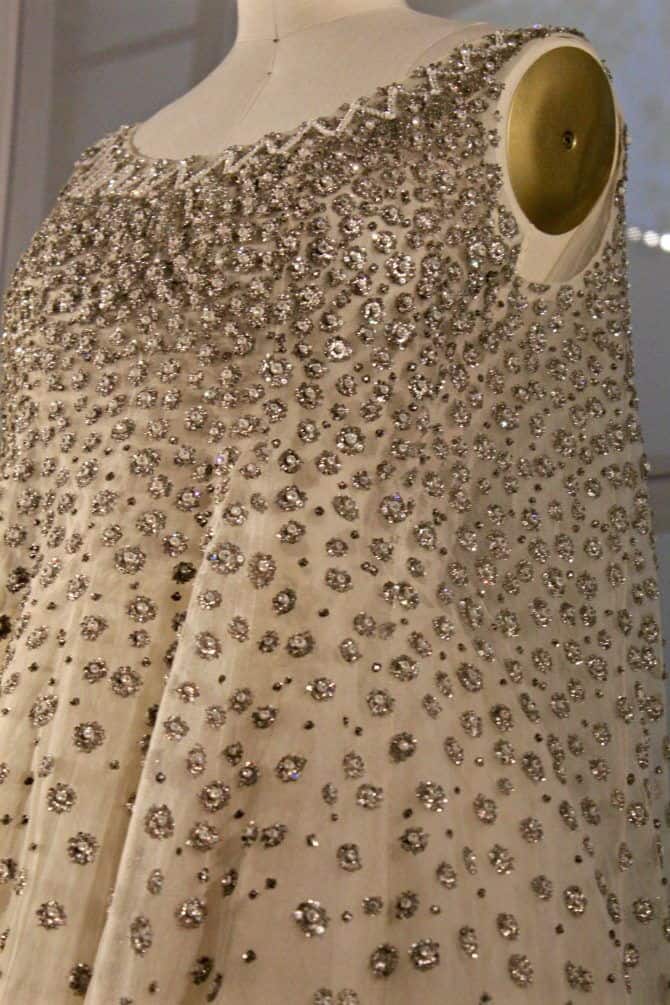

Leather cutwork, one by machine and one by hand, related Alexander McQueen’s Autumn/Winter 2012 ensemble back to French Designer Paul Poiret’s circa 1919 coat. These were two favorites that I kept returning to. Poiret’s (above) Dr. Zhivago collar, meets pastor’s stole, meets puritan dress silhouette was extraordinary. The leather accent was all cut by hand. Below, the dramatic, organic, shape-repeating Sarah Burton (head Alexander McQueen designer) ensemble was perfect-perfection. The shape of the abstract gingko leaf in the cool, sculptural belt, is echoed in the neckline, and in the shoulders as cozy Mongolian wool slopes off. I imagine sweet sounds funneling into the neck and being amplified, as they emerge from the diaphragm and pulse out between the two silver gingko leaves. The laser-cut white pony skin design swirls in orderly, happy collision, giving energy to this incredible piece of art.

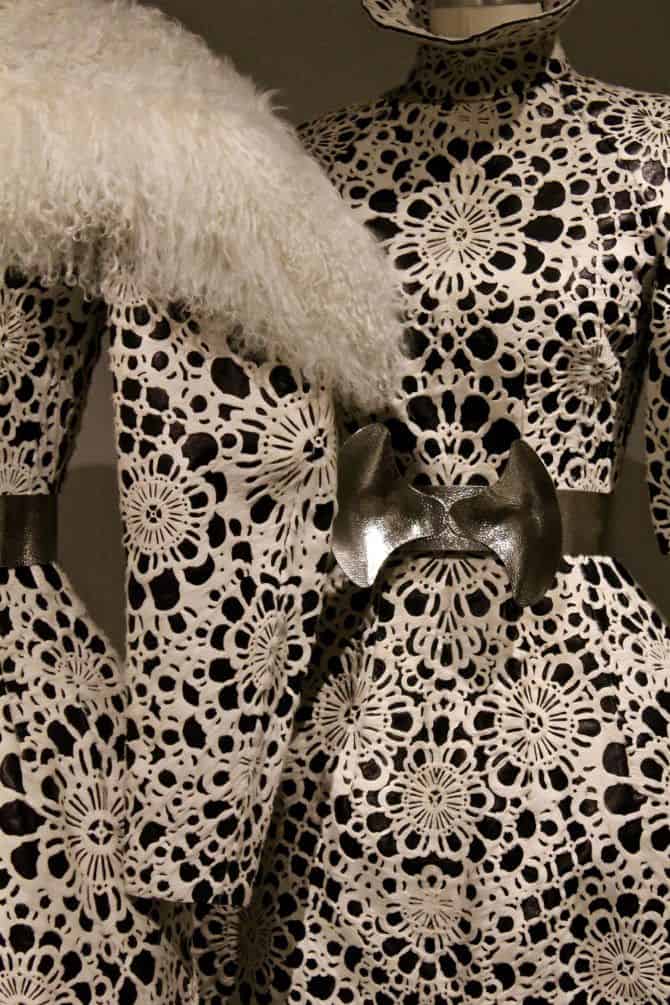

The Manus x Machina exhibition space was designed by the firm OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture). Partner Shohei Shigematsu, described the round centerpiece as, “the ghost cathedral.” This massive space housed the star of the show, only one dress…Chanel’s monastic, maternity, wedding ensemble from Autumn/Winter 2014. The piece de resistance was softly lit by a ceiling dome decorated with a kaleidoscope reproduction of the train’s design. The wedding dress’ spare design invites the attention of the medallion and buttons made of gold, glass, and crystals. The dress is molded out of scuba knit fabric and the incredible train is like a sidewalk paved in gold.

Lagerfeld’s hand-drawn design was digitally manipulated to give it the appearance of a randomized, pixelated baroque pattern and then realized through a complex amalgam of hand and machine techniques.—Exhibit Notes

Head Curator of Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, Andrew Bolton, envisioned an exhibit that liberated the handmade and the machine-made from their usual confines. As I was walking through contemplating defiant techniques, disruptive materials, mastery of humble simplicity, and dedication to detail, I was active in my imagination and my own world. It’s familiar to view machine techniques as basic and standard. Manus x Machina exposed more, presenting technology-enhanced textiles, and fashion materials like resin, or metal filings for artists like Herpen. I was reminded that handwork, often related to lofty beading, embroidery and finish work, is impactful too in its simplest forms–stitches as decoration. The simplicity attracts us like the joy we feel with a great cup of coffee, the smell in the air, a connection with another. Last spring I saw, The First Monday in May, a documentary about the Met Gala and exhibition. In it, Andrew Bolton discusses the pressure to live up to his curation five years ago–Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. The exhibit was the most visited Costume Institute exhibition in the Met’s history, and received critical acclaim. If the emotional power of wonder, and the promise of boundless potential are raised by great art, then Manus x Machina is a masterpiece.

Photos: Dawn Bell Solich